“Flavors of Youth” and the Limitations of Experiencing Art

There are two things you should know about “Flavors of Youth”:

1. It’s a great anime.

2. You probably won’t think it’s a great anime.

“Flavors of Youth” strikes me as an inaccessible anime – particularly to western audiences – and not just because of its meandering, introspective nature that would put a lot of people to sleep. I would describe it as a cultural piece that, to fully appreciate, you not only need to know about Chinese culture, you must have been submerged in it at some point in your life. On top of that, the anime homes in on a very specific Chinese generation: the generation who grew up there around the 90s, the generation who witnessed China’s rise to one of the world’s largest economies. My generation.

Perhaps that’s why I struggle to recall the last anime with which I felt such a deep personal connection. “Flavors of Youth” captures the nostalgic feelings of my childhood spent in 90s China with such authenticity that I was utterly unsurprised to find the chief director is a Chinese close to me in age. If you’re not someone targeted by the anime’s laser-like focus, if you haven’t the life experience of a certain time and a certain place, then “Flavors of Youth” likely feels like a poor man’s Shinkai anime. This view is no doubt enforced by its nature as a work co-produced by CoMix Wave Films, a studio with strong associations with Shinkai. But despite the obvious influences, this anime also stands on its own three feet (because it’s an anthology comprising three stories). With subtle social commentary and Chinese culture permeating through every pore, “Flavors of Youth” is far more than a cheap Chinese knock-off; it possesses its own identity and its own goals, with even the main locations for the stories – Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, the three largest cities in China – carefully chosen as the faces of China’s economic boom.

The central thread that runs through the stories is “youth”. More accurately though, it’s about “seishun”, or “qingchun” in Chinese (they use the same kanji). While those terms seem directly translatable and therefore interchangeable, that’s true only in a literal sense. Words in different languages can have the same literal meaning but vastly different connotations; “seishun”, made up of the kanjis for “green” and “spring”, possesses a certain poetry and an association with a culturally romanticised view of the morning of one’s life, and the word “youth” simply can’t capture the strength of the meanings and feelings invoked by it.

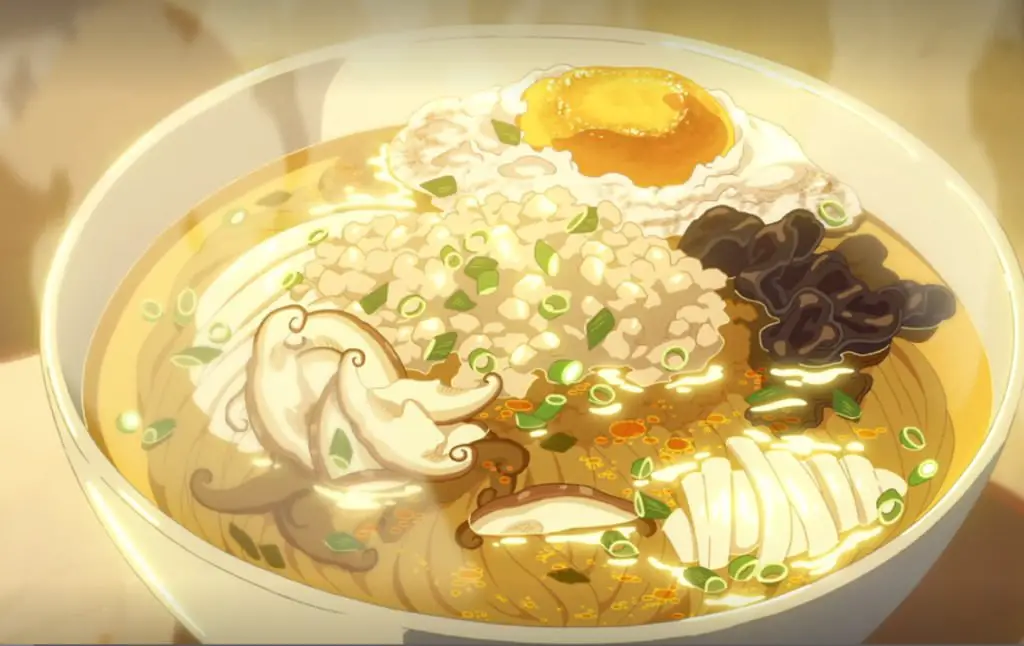

The anthology opens with “The Rice Noodles”, which isn’t so much a story as it is an expression of feelings, subtly blended like the seasonings of a delicious bowl of the titular noodles. The bare premise is about a guy named Xiao Ming (which is, incidentally, probably the most common name for fictional protagonists used in the Chinese education system, frequently seen in example sentences and essays) yearning for the taste of the noodles of his childhood which he ate with his grandmother. The noodles do so much of the heavy lifting in this story that it’s practically the main character – it has strong associations with the memories of Xiao Ming’s grandmother and with the nostalgic days of his seishun, in addition to being a metaphor for the values eroded by China’s rapid economic expansion.

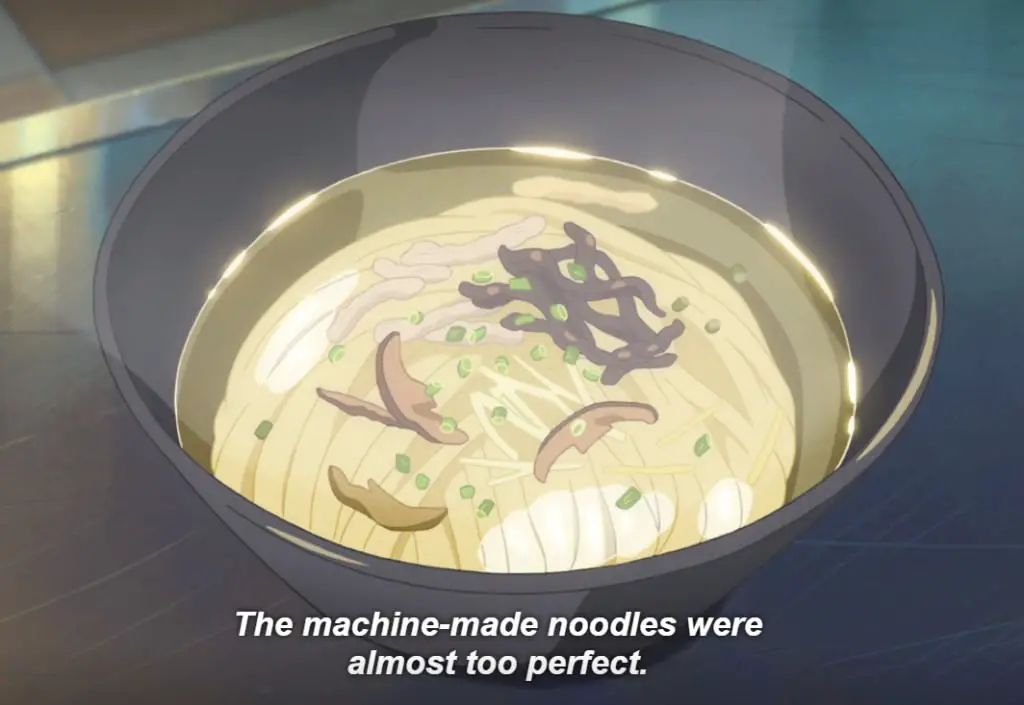

While having practically zero plot, “The Rice Noodles” is thematically rich. To understand the commentary, you need a bit of background. China, like a lot of Asian countries, has a strong food culture – not in the French-esq, fine dining style, but of the local street food variety. The streets and avenues are often dotted with street food stalls and cosy, family-run restaurants serving startlingly good food within tight-knit communities. As the country embarked on a decades-long growth spurt, the local restaurants got gradually replaced by more commercial restaurants and chains, particularly in large cities. On the surface level, Xiao Ming laments that the noodles from the commercial restaurants just aren’t as tasty as the ones he ate as a youth, as they have less of the wholesome ingredients such as wood ear mushrooms. On a deeper level, the anime laments the loss of old values as people chase after money in an increasingly materialistic society.

This isn’t just a case of looking at the past through rose-tinted glasses: China’s economic rise has very much been a double-edged sword. On the one hand, hundreds of millions have been lifted out of poverty, and people’s living conditions massively improved; on the other hand, since adopting aspects of a capitalist system, Chinese society has become a caricature of western consumerism, with people worshiping at the altar of money and material items, and scheming to become rich by whatever means, even at the cost of community, family and moral values. This is why the country’s become plagued by scams and scandals in recent years. Where once people didn’t even bother locking their doors, now they draw their curtains when counting their cash. But let’s pull back from these dark reflections; “The Rice Noodles” does end on a positive note: even as the protagonist acknowledges that he can never recapture his seishun, the fate of the noodle shop brings hope of triumph through adversity, and of the return of non-materialistic values. Sometimes it takes a rough patch in our lives to makes us realise what is truly important.

The visuals play an important part in “The Rice Noodles”, and it’s a precursor of what’s to come, both in terms of strengths and weaknesses in the animation and artwork. “Flavors of Youth” generally looks pretty, in a substandard-Shinkai kind of way, but falls short in the character animation department. This is particularly obvious in “The Rice Noodles”, where the character animation lacks smoothness in some places, and looks overly smooth and mechanical in others. I remember in particular the scenes of people perfectly poised on bicycles, peddling in perfectly cyclical motions and moving forward in perfectly straight lines. But the weaknesses are more than compensated by the details of the background scenery, where the animators managed to capture the streets and buildings of rural and urban China with remarkable fidelity. Even in the visuals, the noodles steal the show: “The Rice Noodles” may not exhibit the scenery porn pervading Shinkai’s works, but it can boast of food porn. I found myself salivating to the beautifully rendered noodles on screen, and could almost smell the aroma wafting from it. The strength of the visuals whisked me away to distant times and places and immersed me in its scenery and atmosphere … but the magic only works because those times and places exist in my memory.

“A Little Fashion Show” tackles the loss of seishun in a more head-on fashion than the other stories, in particular its implication for Chinese women. Age-ism is a problem for women worldwide, especially when it comes to an appearance-based careers like modelling, but Chinese women feel it more acutely than most. While it may seem absurd to say that Yi Lin is raging against the dying light of her career, it’s also fair to say that strong stigmas still exist in Chinese society for women like her, who have reached a certain age without getting married and settling down with kids. And as one of a vast number of career-focused, unmarried women in her generation, Yi Lin is certainly not going gently into that good night. Her story is one of defiance: defiance against an industry’s bias for youth, and defiance against a traditional society’s expectations for women.

But it’s also a story of defiance against something else.

The other topic “A Little Fashion Show” deals with is of family and parenting. And if the first topic I mentioned didn’t resonate with me personally, this one certainly does. Yi Lin lives with her younger sister as their parents had passed away. Tradition dictates that Yi Lin, as the eldest one, should play parent to her younger sibling and take good care of her. And Yi Lin tries to do exactly that. To a fault. During a heated argument between the two sisters, Yi Lin busts out the what is possibly the most memorable line in the whole anthology: “Who do you think I’m doing this for?” This line, along with its classic variant “I’m doing this for your own good” are immortal conversation enders weaponised by Chinese parents against their disobedient children, so I’m sure it triggered a familiar, visceral reaction in many others as it did in me.

Family and Confucian values underpin Chinese society, and children are always expected to be obedient to the parents who pour their souls into raising them, because parents always know best. Of course, that’s not always true, and even when it is, sometimes children need to be allowed to make their own mistakes. The tragedy is that while many of us grew up knowing that, when we become parents ourselves, we often end up acting just like our own parents. In acting as a parent towards her sister, Yi Lin ends up making the same mistake as a typical Chinese parent: she does not realise her sister has grown up, and does not respect her rights to forge her own path in the world.

Ultimately though, “A Little Fashion Show” doesn’t explore the theme of rebellion against suffocating parents too deeply. However, this rebellious spirit roars into life in the third and final story, “Love in Shanghai”.

Better directed, better animated and better written, “Love in Shanghai” is in a different league to the other two stories. Like the headline act of a gig, it finally steps up after the supporting acts have warmed up the crowd. While Shinkai’s influences are rooted all three stories, they go especially deeply in “Love in Shanghai”, all way down to the communication gimmick used as the central lynch-pin of the story. “Love in Shanghai” features the budding romance between the protagonist Li Mo and his classmate Xiao Yu, and its development across multiple snapshots in their lives.

The craftsmanship of the story is impressive, managing to spin an intriguing little mystery around everyday settings. Deliberately paced and carefully plotted, “Love in Shanghai” also delivers at its zenith a perfectly weighted emotional punch. For those reasons, a lot of viewers should find this enjoyable, and certainly more accessible in comparison to the other stories. Nevertheless, I expect those who grew up in China to feel a deeper connection. One reason is the familiarity of seeing overly demanding parents putting academic achievement ahead of everything else. Several scenes depict the literal heavy-handedness of Chinese parenting, and the lack of fuss over them – while may seem shocking or unbelievable to some – is exactly what makes the depiction feel genuine: it really isn’t too far outside the norm.

Straining against the kind of parenting symptomatic of a culture that emphasises strict social order is the burning teenage spirit of rebellion, and it spearheads this last love letter to seishun. “Love in Shanghai” celebrates seishun in all its glory: its inherent ephemeral beauty as well as the emotional baggage; it embraces the flaws of that time in our lives: our hotheadedness, our prideful stubbornness, our naivety, but also acknowledges the purity, the idealistic dreams and fiery determination not yet dampened by the cynicism of experience; and it accepts all of that as part of growing up.

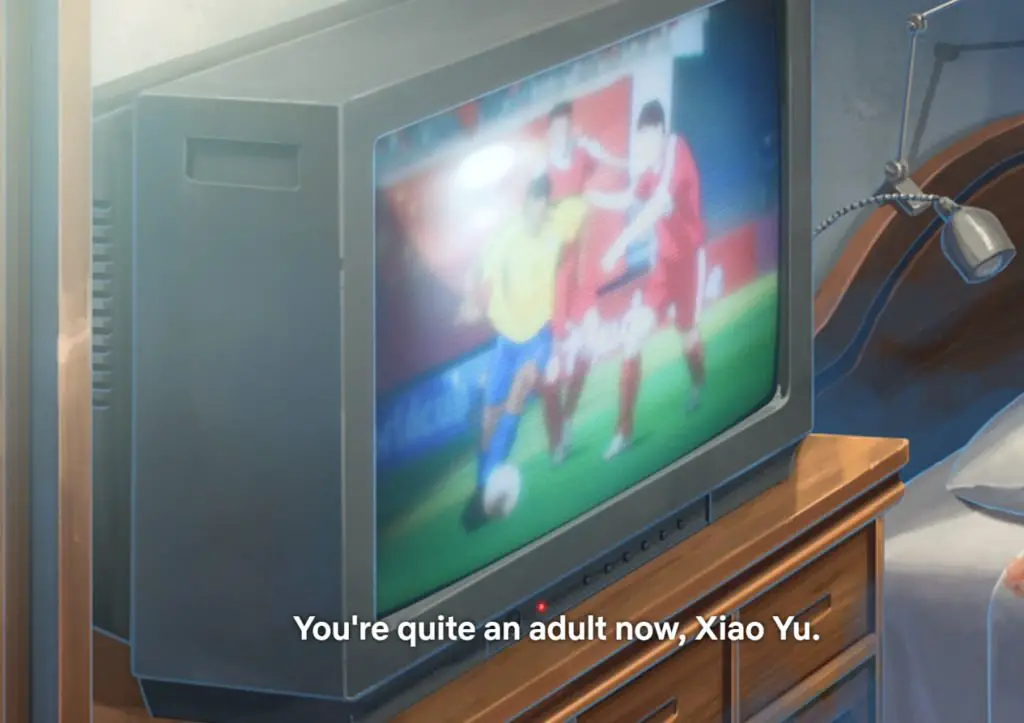

Like the other stories, a lot goes on beneath the surface of “Love in Shanghai”. The spliced timelines exhibit the pace of change in Shanghai over a decade: some shots of the same scenery highlighting the rapid erection of high rises in the city, others of old town areas underlining the rate at which the old buildings gave way to the new. While I did not grow up in Shanghai, the scruffy outward and interior appearances of the buildings felt exceedingly familiar as the same scenes and changes played out in other cities across the country. Despite all the progress, run-down areas still exist in the latest timeline (and even now at the time of writing), their presence exposing the shabby underbelly of a developing nation hiding beneath the veneer of a glittering, modern cityscape. The regeneration of housing is a contentious topic, and one the anime also touches upon, with the sprinkles of dialogue hinting at the tension between the government’s desire to modernise and the needs of people – particularly the older generation – to hold on to something achingly familiar. A brief scene of a TV showing the 2002 football World Cup gives a nod to the first – and so far only – appearance of Chinese men’s team in the finals. Despite being only a couple of seconds long and lacking any related dialogue, the inconspicuous shot subtly marks the landmark event as a source of pride. The amount of information and feelings that “Love in Shanghai” manages to convey through minute details in animation, dialogue and story is simply astonishing.

Shabby exterior

Shabby interior

China vs Brazil in the 2002 World Cup

Shanghai of the 2000s

Shanghai of the 90s

After watching “Flavors of Youth”, I was tempted to make a quip about how, despite being an anime heavily inspired by Shinkai, it affected me more deeply than any of Shinkai’s works. But that’s not really a fair comparison: Shinkai’s anime aren’t tailored to someone with my experiences, whereas this anime is. For example, while I may have understood on an intellectual level how “Your Name.” connects with a people constantly battling natural disasters like the Japanese, as an outsider I can’t really *feel* it. So it’s worth noting the important meta-lesson that “Flavors of Youth” serves up: that our reaction to a piece of art isn’t just down to the art itself, but its intersection with our identity and the lives that we have lived.

So for me at least, “Flavours of Youth” is a great anime.

Personal rating: +2.0 (great)